Clear communication requires using the proper verb tense in writing your manuscripts. Verb tense organizes actions in time and emphasizes your point.

Verb Tense Writing Tips

In any scientific manuscript, sequence and timeline are important. For example, your experiments precede your summary of the results and outcomes. Further, the work of other scientists likely preceded your current work, and discussion of these previous findings adds dimension to your manuscript. In addition, if you are attempting to show instances of cause and effect, it’s important to note what came first and what subsequently resulted.

- Using the correct verb tense clarifies the timeline of your research and process.

- Incorrect verb tense can confuse the reader about the sequence of your arguments.

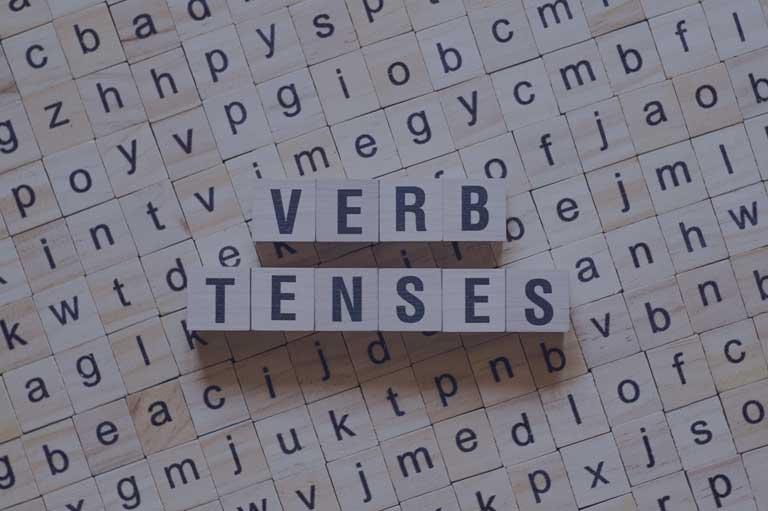

- In the English language, there are 12 verb tenses.

| Time | ||||

| Group | Description | Past | Present | Future |

| Simple | action occurring now | I filled the flask | I fill the flask | I will fill the flask |

| Continuous | action that was/will be in progress | I was filling the flask | I am filling the flask | I will be filling the flask |

| Perfect | action has been completed | I had filled the flask | I have filled the flask | I will have filled the flask |

| Perfect Continuous | action that started in the past and continues | I had been filling the flask | I have been filling the flask | I will have been filling the flask |

The present tense shows that an action is taking place in the present, but does not indicate when the action will end. You may also use the present tense to describe a fact that is universally true and not limited to a particular time. For example:

Infected hosts differ in their responses to pathogens; some hosts are resilient and recover their original health, whereas others follow a divergent path and die.1

The past tense indicates that an action was completed in the past, while the future tense shows action that is yet to be completed–more of a prediction than a statement of finished reality. In the example below, the researchers used past tense to discuss their proposed thesis, and then the future tense to highlight its predictions.

We started (past tense) with the proposition that infected patients will trace (future tense) a path over a multidimensional manifold in disease space; resilient patients will travel (future tense) predictable paths as they sicken and recover, and patients who do poorly will also take (future tense) predictable paths when they sicken and die.1

Verb tense for each section of a journal article

In science manuscript writing, specific verb tenses are standard for each manuscript section.

Abstract

The Abstract will usually contain a mixture of verb tenses, as the background is generally based on published findings, which are presented in the present tense. The methods, results, and conclusion are presented in past tense.

Introduction

The Introduction section of your manuscript is your explanation of previous findings that led to your question. The Introduction mainly discusses previously published research that is currently accepted as fact; thus, these findings are presented in the present tense. For example:

Rheumatoid arthritis is (present tense) a common autoimmune disease primarily manifesting as chronic synovitis, subsequently leading to a change in joint integrity. Progressive disability and systemic complications are (present tense) strongly associated with a decreased quality of life.2

In the Introduction, you may also use a mixture of past tense and present tense to indicate why you are performing your research. For example:

Pain relief is (present tense) a major goal in the treatment of RA, but is only partly achieved (past tense) by NSAIDs or opioids.2

Methods and Results

Methods and Results, on the other hand, are always written in past tense as they describe what you have done and what resulted. Figures and Table legends are referred to in the present tense.

“Figure 1 shows…”. not “Figure 1 showed…”. The only time you would write “Figure 1 showed…” is if you were referring to a Figure 1 from another paper, e.g., “In Thompson and Thompson, 1989, Figure 1 showed…”

Discussion

The Discussion will also include a mixture of tenses as you discuss previous findings (present tense), your findings (past tense), and introduce your plans for further studies (future tense). Using the correct verb tense clarifies what was known before your study and what your study contributes.

Conclusion

Verb tense errors can divert your readers’ attention from your manuscript’s valuable content. Select the appropriate tense to effectively convey your research. Change tenses only when there is a genuine temporal shift. When discussing actions occurring simultaneously, maintain consistent tense throughout associated verbs. Following these straightforward guidelines ensures clear communication with your readers.

References

- Torres BY, Oliveira JHM, Thomas Tate A, Rath P, Cumnock K, Schneider DS. Tracking resilience to infections by mapping disease space. PLoS Biology 2016; 14(4): e1002436.

- Meier FM, Frerix M, Hermann W, Muller-Ladner U. Current immunotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunotherapy 2013; 5(9):955-974.